Free Mohammed El-Halabi

September 8, 2022

New Israeli Regulations Pave the Way for the Ethnic Cleansing of Area C of the West Bank

September 16, 2022Is insisting on universal principles of combatting discrimination and racism a denial of the uniqueness of the Holocaust?

First published in Canadian Dimension

https://canadiandimension.com/articles/view/walking-into-a-minefield

Photo: Palestine solidarity campaign demonstration in Ireland. Photo from Flickr.

Canada recently enacted the following amendment to its criminal law. Section 319 of the Criminal Code now states:

(2.1) Everyone who, by communicating statements, other than in private conversation, wilfully promotes antisemitism by condoning, denying or downplaying the Holocaust (a) is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two years; or

(b) is guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction.

I am a Palestinian whose entire existence has been impacted by the world’s reactions to the Holocaust, therefore the issue of the Holocaust and how it is viewed and interpreted is of vital importance to me. Much of the Western world, as well as the Jewish community worldwide, has been persuaded that the creation of the State of Israel was the proper and legitimate response to the horrors of that momentous event.

After the Holocaust, the Zionist movement pushed to create a Jewish state and to provide it with enough support and legitimacy to ensure its mission as a proper response to the greatest evil in modern history—and the best vehicle available to prevent its recurrence.

This view of the Holocaust would justify not only what was done to my people, but also Israel’s possession of nuclear weapons, a robust arms industry that supplies some of the most notorious regimes, an aggressive military posture, as well as exemptions from the normal rules of ethics and international law that would apply to other countries. It would also justify the practice of apartheid, and would render criticism of the State of Israel, and advocacy of equality for Palestinians, to be a form of antisemitism and therefore illegitimate since it would interfere with the function of the Jewish state, and therefore imply the downplaying of its significance.

At the heart of this interpretation is that the Holocaust is a unique event that warrants singular treatment, and that by extension the State of Israel as a response to the Holocaust intended to prevent its recurrence, is exceptional, and should not be judged by standards and norms applying to other states.

The ethnic cleansing committed against my people during the Nakba, or “catastrophe,” in 1948, as well as the current apartheid system practiced in my homeland is both excused and legitimized by the need to have a Jewish state as a specific and concrete response to the Holocaust.

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, including the examples issued with it, conflates opposition to Zionism and the state of Israel with antisemitism. The new amendment to the Criminal Code follows the same path and enshrines in Canadian criminal law this understanding. Drawing different lessons from the Holocaust which do not support that political mythos can be seen as “downplaying” the Holocaust and therefore runs afoul of that law.

This is a serious problem to me. What does “downplaying” mean? Is mentioning other genocides illegal? Is drawing attention to suffering by others at the hand of Israel akin to downplaying the Holocaust? I have been specifically told by one Christian Zionist that not until six million Palestinians die can I appeal to his sympathy or support. Is insisting on universal principles of combatting discrimination and racism a denial of the uniqueness of the Holocaust?

To be sure, the Holocaust was a monumental event, and the drive to prevent its recurrence is an unquestionably worthy project to be pursued by all. The utter evil of Nazi genocide is one of the most vivid examples of man’s inhumanity to man. But the lessons we learn from it, and the consequences of our remembrance, are crucial. Is our memory to be used to empower the State of Israel and exempt it from ordinary norms, or is it to be used to urge universal respect for human rights and international law, with a fierce determination that such a calamity should never again be allowed to befall anybody?

I am a radical believer in free speech who believes false ideas should be challenged and refuted by logic, evidence, and persuasion, not censored and criminalized. Those who choose to deny the historic facts surrounding the Holocaust (or the Nakba, for that matter) are fools. Often the best response to false ideas is to subject them to the ridicule they deserve. For the record, the historical facts of the mass murder and genocide of Jews by the Nazi regime are well documented and do not need my or anyone else’s affirmation.

The mere fact that I need to make this statement to avoid criminal persecution is itself chilling and should be of concern to all Canadians, including those most eager to fight antisemitism, racism and prejudice. Criminalizing the promulgation of false ideas simply lends credibility to conspiracy theorists. The best response to such falsehoods and denials should be truth, evidence, and rational argument—not the censorship or criminalization of critical ideas.

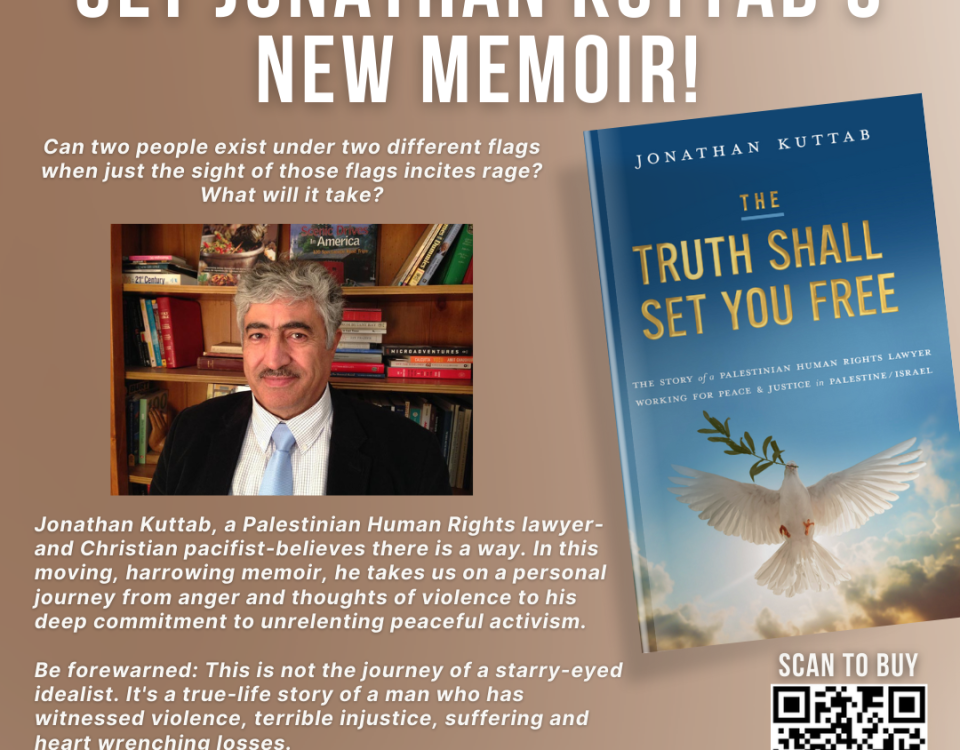

Jonathan Kuttab is a co-founder of the Palestinian human rights group Al-Haq and co-founder of Nonviolence International. A well-known international human rights attorney, Jonathan practices in the US, Palestine and Israel. He serves on the Board of Bethlehem Bible College and is President of the Board of Holy Land Trust. Jonathan was the head of the Legal Committee negotiating the Cairo Agreement of 1994 between Israel and the PLO. After graduating with his Doctor of Jurisprudence (JD) from Virginia Law School, and practicing a couple years on Wall Street, Jonathan returned home to Palestine. Jonathan was visiting scholar at Osgoode Law School at York University in Toronto in the Fall of 2017, and is a founding director of Just Peace Advocates Mouvement pour une Paix Juste, a Canadian based international law human rights not-for-profit organization. Jonathan is currently the executive director of Friends of Sabeel North America (FOSNA).