More from Jonathan Kuttab, from the Arab Center Washington DC & other

December 1, 2020

Videos from Various Speaking Engagements

December 30, 2020Original posted by Arab Center Washington DC

On November 17, the Palestinian Authority’s minister for Israeli affairs, Hussein Al Sheikh announced on Twitter that the PA decided to resume coordination with Israel. This was not surprising to many in the occupied West Bank and other Palestinian areas since the original decision last May by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas to suspend said coordination was not fully carried through and indeed continued in security matters. The network of interlocking relationships between Israel and the Palestinians could not be easily undone with a mere public announcement about suspension. Perhaps the election of Joe Biden and the public expectation that the new administration will resume funding for Palestinian projects, reengage with the Palestinian Authority, and revive the moribund “peace process” provided good excuses to climb down from the tree of “suspended coordination” despite the potentially high price among Palestinians.

It is true that Abbas and the PA were under great popular pressure to suspend coordination with Israel, especially that over security, but those who demanded the suspension showed little understanding of the intricate interconnections between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. The suspension cannot be thought of as an automatic mechanism that Palestinians can activate once they see that Israel is not abiding by the basic tenets of the relationship as codified by the Oslo Accords of the mid-1990s. To be sure, if Palestinians hope to impact their unequal relationship with Israel in their own favor, they have to undergo a fundamental rethinking of the entire Oslo process and the very nature of the Palestinian Authority itself.

Security Coordination

Security coordination is first and foremost of vital interest for Israel and perhaps the raison d’être for the very existence of the PA as far as many in Israel are concerned. Annexes to the Agreement between Israel and the PLO prescribe in detail the number, weapons, and locations of deployment of the Palestinian police, the matters that need security agreement, and coordination between said police and Israel. The most obvious feature of the security coordination are weekly, and in some instances daily, information-sharing meetings at local and national levels between Israeli and Palestinian security personnel. While the results of this coordination are not broadcast, it has prevented many attacks on Israeli targets and led to the arrest or killing of many Palestinian activists. It is quite possible that some within the PA use security cooperation to gather intelligence about and advantage over Hamas with which the PA has been at odds since 2007.

The most obvious feature of the security coordination are weekly, and in some instances daily, information-sharing meetings at local and national levels between Israeli and Palestinian security personnel.

This security coordination continued even when the relationship between Israel and the PA was at its very worst and despite President Abbas’ repeated threats to end it. Even during the last pronounced suspension, occasional reports in the Israeli media strongly suggested that coordination between the two parties was continuing. Both sides apparently felt it was embarrassing to the PA, and not politically useful for Israel to contradict Palestinian officials on this point or to publicly brag about the security cooperation. This security coordination is particularly sensitive for Palestinian activists who are ashamed that “their” police act as agents for Israel against Palestinian activists. Such a role, in their view, better befits traitors and collaborators, than their own legitimate representatives.

Coordination on Civilian Affairs

Of more direct impact on the lives of ordinary Palestinians is the coordination on civilian matters. Under the military regime that existed in the occupied territories prior to the Oslo Accords, all aspects of life were strictly controlled and regulated by a system of permits and licenses administered by the Israeli Civil Administration. The Oslo agreements stipulated a gradual transfer of authority over many matters in the occupied territories from the Civil Administration––which was supposed to be dissolved––to the Palestinian Authority. In the interim, Israeli military officers of the Civil Administration continued to conduct affairs and exercise the powers of the different ministries under Jordanian law. But some of the powers gradually transferred to the PA were in the beginning vested in “Joint Committees” that exercised those functions. Other powers remained solely in the hands of the Israeli authorities more directly.

In reality, Israel as an occupying power continued to hold all true authority and many Palestinian affairs that were not directly administered by Israel were delegated to Joint Committees or District Coordinating Offices (DCO’s).

In reality, Israel as an occupying power continued to hold all true authority and many Palestinian affairs that were not directly administered by Israel were delegated to Joint Committees or District Coordinating Offices (DCO’s) which took the place of offices of the Civil Administration in many areas. At these offices, which flew Palestinian and Israeli flags, Palestinian and Israeli officials were to view all applications and issue permits and licenses. Even where the PA ran local affairs within areas A (where the PA exercised full control according to the Oslo process) and B (Palestinian civil control but joint Palestinian-Israeli coordination), a large number of permits still required coordination with Israel, which continued to hold veto power within the joint committees. However, these committees had no authority over Jewish settlers in the occupied territories, or over matters that were of vital interest to Israel which administered them directly without Palestinian participation.

As the de facto power on the ground and in the joint committees, Israel continues to exercise its full authority over Palestinian civilian affairs. The following is a partial list of the issues that continue to require Israeli permissions and licenses:

- All imports and exports from and to the West Bank, including movement of goods between the West Bank and Gaza, and between them and Israel, because Israel continues to hold all borders and points of entry and exit;

- Collection of customs duties on imports going to the Palestinian market: Since Israel controls all borders, it collects all customs duties on behalf of the PA and then passes them on after keeping an administrative fee. Israel has often withheld those funds for political reasons;

- The issuance of radio and TV licenses, and designation of frequencies for broadcasting as well as cellular phone services;

- Value added taxes (VAT) refunds and offsets: The Israeli military imposed VAT taxes on the West Bank. The Economic Protocol of the Gaza-Jericho Agreement of 1994 requires Palestinians to maintain the same system Israel has and at a rate equal to or no more than 1 percent below the Israeli rate. Since Israel is by far the largest trade partner of the Palestinian territories, merchants and consumers need to obtain refunds of VAT fees Israel collects on their goods, and to offset their own tax receipts against VAT due to Israeli merchants through an offset banking mechanism. With the tax currently at 17 percent, it is a major element in every commercial transaction in the West Bank. Israeli recognition and acceptance of VAT receipts issued in the Palestinian territories is thus vital;

- Postal services: All mail services must pass through (and be inspected by) the Israeli postal authorities. Israel actually vetoed the first batch of postal stamps issued by the PA and has exercised the right to view the images on all stamps issued since then. A recent picture in the press illustrated that ten tons of bags of mail addressed to residents of the Palestinian areas were held up by Israel for over 8 years;

- Banking and currency: Israeli currency is the official tender in PA areas, and all Palestinian banks must go through the Israeli Central Bank to complete their transactions. Israel has used this fact as leverage to order Palestinian banks to close accounts of prisoners and their families as well as those belonging to Hamas and Hamas affiliated organizations. Those who violate these regulations risk up to 7 years’ imprisonment;

- Population register: All Palestinians over the age of 16 under Israeli occupation are required to carry numbered identity cards (hawiyya) issued by the Central Register of Population. The Population Register and its computers are in Israel and no card or travel document can be issued or renewed by the PA and unless all births, marriages, changes of address, or status have been recorded in it. All transactions as well as travel within the Palestinian Authority areas require the identity card number;

- Travel to East Jerusalem, Gaza, Israel, and the outside world: Palestinians from the West Bank have extensive relations and need to travel for family, economic, and health reasons, religious services, access to foreign embassies and consulates, and education, among others. Even travel within the occupied territories (to the settlements, and frequently to the Jordan Valley, as well as agricultural lands on the wrong side of the Separation Wall) requires Israeli permits. The Oslo Agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) specified that Israel must treat Gaza and the West Bank as a single territorial unit, but this provision seems to have fallen by the wayside, and travel for whatever purpose within these areas requires a permit. Even Palestinian police units cannot move between the cities and the villages of the West Bank without prior coordination with the Israelis since Areas A and B consist of a number of non-contiguous areas separated by swaths of land which are under Israel’s total control.

During the Second Intifada, Palestinian officials were expelled from the Joint Committees as well as the Allenby Crossing, which put these buildings under the exclusive domain of Israeli officials. The Palestinian flag was removed and access to these offices was controlled exclusively by Israel. Officials from the PA were then allowed to return but as supplicants, sometimes on a weekly basis, to bring the requests and petitions of the population to the Israeli officials and to take back the approvals or rejections as the case may be. Occasionally, Palestinian civilians would be individually summoned to these offices and would wait hours until they are allowed entry. These offices would also serve the Israeli security services personnel who would interview Palestinian applicants, try to recruit them as informers, or even arrest them when they showed up for their interviews.

It was mostly this civilian coordination that was suspended last May and it led to hardships as Palestinian births were no longer recorded in the Population Register and medical and other permits were no longer processed through the Palestinian Authority coordination officers, although some coordination apparently continued to take place. The Israelis transferred authority over the troublesome electricity stations in the West Bank to the PA, and they famously allowed the late Saeb Erekat to go to an Israeli hospital for treatment when he was diagnosed with COVID-19 and his situation worsened. All elements of the coordination that served Israel rather than the Palestinians seem to have continued unabated.

While the PA attempted to declare victory and imply that certain concessions were obtained when it resumed coordination last November, the local population was not too enthused.

While the PA attempted to declare victory and imply that certain concessions were obtained when it resumed coordination last November, the local population was not too enthused. It is more likely that the PA capitulated and would pay an even higher price before it obtained the benefits from resumed coordination. It is no wonder, then, that PLO Executive Committee Hanan Ashrawi resigned after the announcement of resumed security coordination between the PA and Israel. Apparently, she, and the rest of the population, were looking for a radical change in the relationship, a change that clearly is not being seriously considered at this time.

The Task Is Hard

Suspending PA-Israel coordination is not simple because both the cooperation arrangements are so extensive and embedded and changing them would be contrary to Israel’s interest. To change this relationship, the PA must be ready to enter into a major confrontation with Israel and to pay a heavy price for it. Steps by the Biden Administration to relieve some of the pain felt by Palestinians and to relaunch some sort of a process may be all that the PA can expect at this point. The people of Palestine, however, are looking for a more meaningful and radical change. To bring that about, there is a need for new elections and for a genuine end to the internal conflict between Fatah and Hamas that unifies Palestinian ranks.

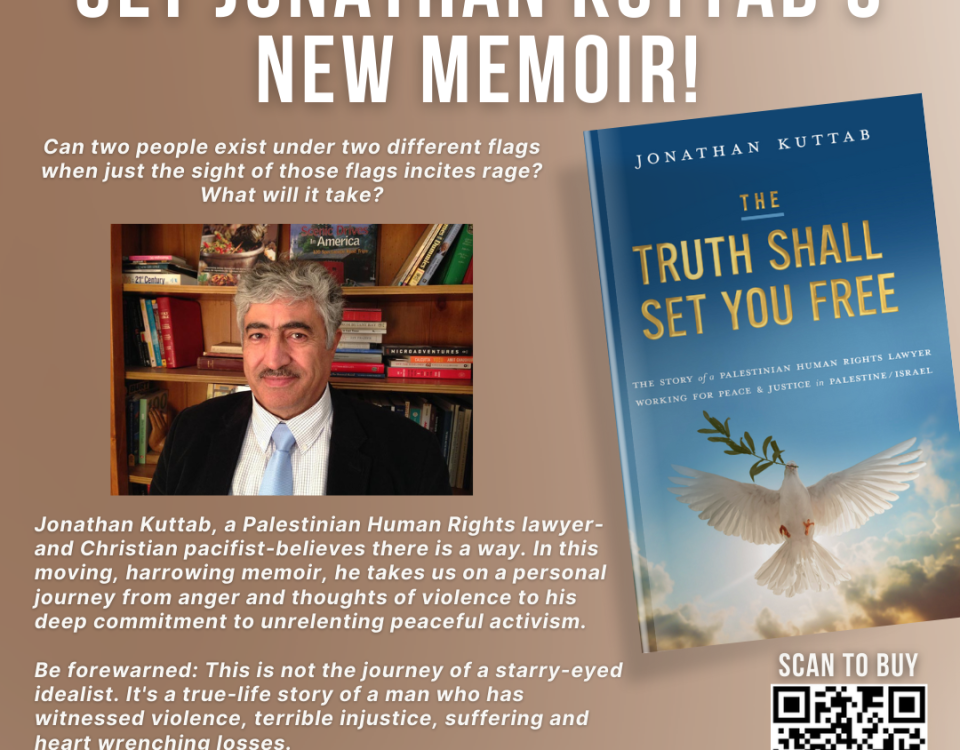

Jonathan Kuttab is a leading human rights lawyer and a Non-resident Fellow at Arab Center Washington DC. He is a resident of East Jerusalem and a partner of Kuttab, Khoury, and Hanna Law Firm there. He is the co-founder of Al-Haq, the first international human rights legal organization in Palestine, and of the Palestine Center for the Study of Nonviolence.